Hidden Mother Photographs – Behind the Scenes of Early Photography

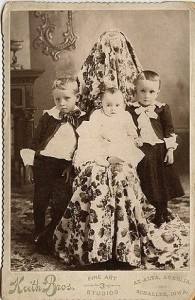

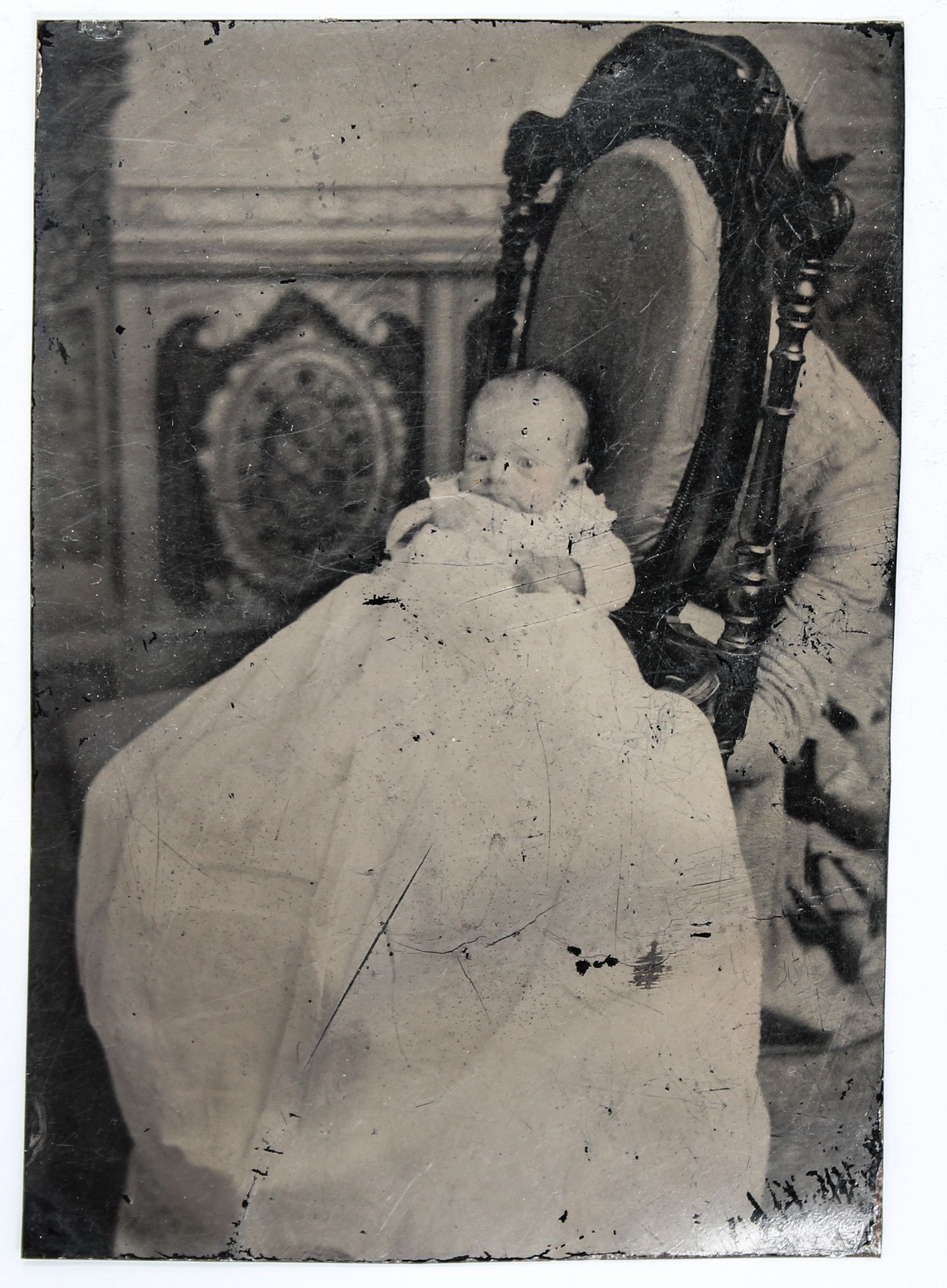

We recently came across this “Hidden Mother” tintype, just in time for the Halloween season. At first glance, the tintype is simply a charming portrait of a baby. On closer inspection, you can see the half-hidden form of the child’s mother crouching behind the chair. Some people find Hidden Mother photographs a little creepy, but they’re also a really great look behind the scenes of early American photography.

We recently came across this “Hidden Mother” tintype, just in time for the Halloween season. At first glance, the tintype is simply a charming portrait of a baby. On closer inspection, you can see the half-hidden form of the child’s mother crouching behind the chair. Some people find Hidden Mother photographs a little creepy, but they’re also a really great look behind the scenes of early American photography.

The first publicly announced photographic process was the daguerreotype process, invented by Louis Daguerre. The process required several minutes of exposure in the camera and produced beautifully clear and detailed images. In a daguerreotype, the image is developed on thin silver-plated copper sheets and has a reflective quality that can make it look like the image is floating above the metal’s surface. The surface of the image is quite delicate and would be covered with a protective sheet of glass. Creating a daguerreotype was expensive and time consuming, and by the 1860s it had mostly been replaced by newer, more practical processes like the tintype.

A tintype, also known as a ferrotype, is easily identifiable: the photograph is on a thin sheet of metal coated with a dark lacquer or enamel. While a tintype has a metallic sheen, it is not highly reflective like a daguerreotype and has a noticeably darker tint overall. The tintype process was quick, inexpensive, and durable, and proved to be an immediate public success: a person could sit down, have their photo taken, and walk out with the tintype mere minutes later.

Although tintypes required a shorter exposure time than daguerreotypes, it was a far cry from today’s instant photography. The exposure times could last anywhere from 10-40 seconds depending on the light, making it challenging to photograph small children. The solution for 19th century parents who wanted a clear, non-blurry photograph of their child was the “Hidden Mother” (also sometimes known as “Ghost Mothers”).

Hidden Mother photographs can be found across the spectrum of early photographic types: daguerreotypes, tintypes, and ambrotypes. The photographs may have a disembodied hand reaching out to steady an infant propped up in a chair, or the edge of a mother’s body may be visible as she crouches (mostly out of sight). In other less subtle photos, a child will be seated on her mother’s lap while the mother is entirely covered with a large cloth draped over her head and body. Perhaps the most unnerving of the Hidden Mother photographs are the ones in which the mother’s face was visible in the final photograph– and was then scratched out and obliterated. The photographs would often be mounted or framed with an oval mat to obscure the mother’s form even more.

Tintypes were a popular choice for family portraits in the late 19th century, and retained their popularity, particularly at tourist destinations, well into the 1940s. Tintypes were inexpensive and readily available to nearly everyone, ideal for capturing a child’s first photograph. Hidden Mother photographs are a fascinating and collectible look behind the scenes of the ingenuity used to overcome the technology’s limitations and achieve the perfect child’s portrait.